Sir Arthur George Tansley, 1871–1955

The linked pages provide a short introduction to the life and achievements of Sir Arthur Tansley, founder of New Phytologist.

For a more in-depth biography please read the book Shaping Ecology: The Life of Arthur Tansley by Peter Ayres, former Editor-in-Chief of New Phytologist.

The Man

Tansley provided his generation of botanists with a vehicle for exchanging information and opinion when, in 1902, he founded the New Phytologist. He was only 30 years old. His influence grew steadily and he is now recognised as the father of British ecology.

His drive helped found the British Vegetation Committee, which in 1913 evolved into the British Ecological Society. He was its first President and soon Editor of its Journal of Ecology. He served immediately after WWII on the government committee looking at the establishment of national nature reserves. The outcome was the establishment of the Nature Conservancy in 1949. Tansley was its first Chairman. He was already President of the Council for the Promotion of Field Studies (now the Field Studies Council).

|

|

|

The first issue of The New Phytologist was published in January 1902, replacing the ‘British Botanical Journal’. Read the editorial by Tansley and papers in the first issue. | The British Islands and Their Vegetation, 4th edition. The first edition was published in 1939. | Britain’s Green Mantle, 2nd edition. The first edition was published in 1949. |

From small beginnings – research papers on the tissues that conduct water in mosses and ferns – Tansley’s writing grew in scope and ambition. His principles of ecology – most notably the ecosystem – shaped the emergent science both in Britain and throughout the world. The British Islands and their Vegetation (1939) distilled for ecologists his lifetime’s work, while Plant Ecology and the School (1946) and Britain’s Green Mantle (1949) helped popularise ecology among the wider public. View a complete list of Tansley’s publications in the publications tab.

Happily acknowledging his debts to the Alsacien botanist, Andreas Schimper, and the Dane, Eugen Warming, Tansley changed their plant geography into his ecology. His general approach and overarching theories provided a model that was adopted across Europe and in N. America.

Attracted in mid-life to psychology, and following publication in 1920 of his The New Psychology and Its Relation to Life, Tansley studied with Sigmund Freud in Vienna. For full details, please visit the Tansley and Psychoanalysis section. He wrote other landmark articles in psychology (see publications) but the centre of his attention eventually returned to botany. Psychoanalysis helped shaped his personal philosophy.

Ecological theory was moulded to suit different interpretations of the way the wildlife and peoples of the British Empire had evolved, and should be managed. Peder Anker considers Tansley’s work from social psychology to ecology.

Tansley and New Phytologist

The promotion of botany through improved communication between botanists was Tansley’s aim as he founded The New Phytologist. It was the same goal he sought, by various means, throughout his working life.

The New Phytologist was his first success. Just turned 30, and an assistant lecturer at University College, London (UCL), he recognised that botany was held back by a lack of opportunity for publication and discussion. He wanted a means of communication through which like-minded young botanists could share their knowledge and experiences for mutual benefit. With £130 from his own pocket, and using a cheap printer in a back street off London’s Tottenham Court Road, he launched the new journal in 1902. Subscription was 10 shillings (£0.5) a year for 10, very thin, issues. His instincts were proved right. Within two years, The New Phytologist was paying its way and he had recovered his investment.

A young Arthur Tansley (bottom, far left) at the meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science held in Glasgow in 1901 (reproduced with permission from the University of Glasgow). For a list naming many of the people who appear in this photograph please see 'The ‘Tansley Manifesto’ affair' by A.D. Boney (1991).

Tansley wanted ‘...a medium of easy communication and discussion between British botanists on all matters…including methods of teaching and research’. Publication should be rapid, allowing the swift appearance of new observations otherwise liable to be lost. Short notices of important new books and papers were to be a regular feature, as were short reports of meetings of botanical and biological interest, foreign as well as domestic. The New Phytologist was to be THE forum for botanists.

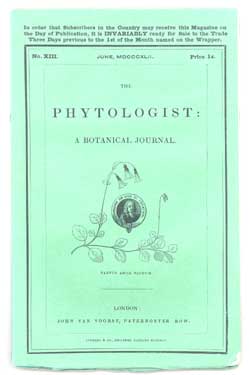

Tansley almost called his offspring the British Botanical Journal but, following the suggestion of Francis Wall Oliver (Professor at UCL, and his immediate superior), settled on a more memorable name, The New Phytologist, after the magazine-style Phytologist that had enjoyed a short life between 1842–1863.

Although ecology was especially well represented – at least until the Journal of Ecology was launched in 1913 – Tansley was adamant that in its pages The New Phytologist should include all aspects of botany. To this day, and unusually, the journal remains ‘broad spectrum’. One basic tenet was, however, soon abandoned: the journal became international. The change reflected not just the journal’s appeal, but also Tansley’s travels and widening circle of contacts, in particular, as he organised the first International Phytogeographic Excursion. See the section on Tansley’s life events.

Tansley was a frequent contributor to early volumes, both in his own name, and anonymously as Editor. He was not afraid to use ‘his journal’ as a pulpit from which to preach his view of the future of botany. Most famously, in 1917, he encouraged the ‘Botanical Bolsheviks’ (including his brother-in-law, F. F. Blackman) to publish ‘The reconstruction of elementary botanical teaching’, which became known as the ‘Tansley Manifesto’103. Controversially, the Manifesto argued that plant physiology should be much more prominent in elementary teaching, and the newer disciplines of ecology and genetics should be properly represented. The Manifesto successfully persuaded a generation of younger men and women to modernise the botany they taught in British universities.

The Phytologist: A Botanical Journal. Front cover of the journal as published in June, 1842.

At the end of 1931, Tansley passed on the editorship of his flourishing journal to three good friends and distinguished younger botanists: Roy Clapham, Harry Godwin and Will James. Similar handovers have occurred several times since then123. The New Phytologist continues to flourish in the 21st century.

New Phytologist front cover from Volume 206, Issue 1 (2015).

A.G. Tansley – the founding figure of British ecology

By John Sheail, NERC Centre for Ecology and Hydrology, Wallingford, UK.

John has written a history of the British Ecological Society and several books on the history of conservation and the environment movement.

Tansley’s career encompassed the late-nineteenth century emergence of British ecology, its long, hesitant development, and ecology’s eventual recognition through the establishment of the Nature Conservancy in 1949, an ecological research council of which Tansley was founder-chairman. Conscious of how he was neither a taxonomist nor experimentalist, Tansley brought rather a continuing preoccupation with philosophy and processes of thought in that emergent natural-science. As noted elsewhere on this site, social scientists have highlighted his promotion of Freudian psychology, and a perceived impact within the power politics of imperial resource-development. Harry Godwin, his principal biographer, remarked, Tansley ‘concealed in himself the potentialities of many personalities, or at least several careers’115,116. Whatever the particular pursuit or sentiment, he strove for the rigour which merited scholarly and public recognition.

Tansley was blessed with both financial independence and a ‘plasticity’ of mind which prevented, so Francis Wall Oliver wrote in 1912125, his ever growing ‘old fashioned’. Arthur George Tansley was born in August 1871, the son of a London ‘high-class’ furniture manufacturer. Besides inheriting ‘the best qualities of a late Victorian liberal, free thinker and humanist’, he had the business acumen to found, sustain and edit The New Phytologist in 1902, the year of his father’s death. His marriage, a year later, to Edith Chick (daughter of a Honiton lace-merchant, and a student of botany at University College, London, UCL) brought a lifetime’s support, giving him the opportunity, for example, to resign his Cambridge post in 1922 for the greater freedom to write and study.

Tansley had left school to attend classes at UCL where he so impressed Frank Oliver, the professor of botany, that, while still a student at Trinity College, Cambridge, Tansley became the Quain postgraduate Student (1893–1895) and thereafter Oliver’s assistant. He uninterruptedly obtained a first-class degree in the Cambridge Tripos examinations and helped establish UCL as a leading centre for botanical teaching. Tansley took up Oliver’s anatomical interest in fern-like plants, his studies in the evolution of the Filicinean vascular system securing him a Cambridge lectureship in 1906.

A stimulus to the founding of New Phytologist was Tansley’s recognition of the need at that time for a journal which would publish those observations and views for which there was neither the time nor means to enable them to be worked up into an elaborate paper, but which might ‘afford a much needed help or clue to some other investigators’117. Although regretting not having studied in a leading German laboratory, like many of his contemporaries, his close reading of the continental literature prepared him well for that other commonplace-maturation of the academic botanist, an overseas’ study-tour. He spent the greater part of 1900-1901 in Ceylon, the Malay Peninsula and Egypt. While collecting research material as a plant anatomist, he became fascinated by the different plant communities encountered. He had, prior to the tour, made Warming’s Oekologische Pflanzengeographie141 the basis of a course of university extension-lectures. He secured six contributions to a series of ‘Sketches of Vegetation at Home and Abroad’, published in the first 10 volumes of New Phytologist, Tansley co-authoring one such ‘Sketch’ on Ceylon coastlands13. He pressed for more studies of the ‘plant communities nearer home’, writing as early as 1902 of how, once initiated, ‘the fascinating nature of the work would ensure its continuance and propagation’6.

Tansley’s paper, ‘The problems of ecology’11, which prefaced a morning session, given over to botanical survey, at the British Association’s annual meeting of 1904, became British ecology’s foundation-paper. His purpose was to demonstrate, before so large and distinguished an audience, how its practitioners must consciously strive for rigour. Ecology was still grappling with the first of the two stages of development in any natural sciences, namely with descriptive survey and explanation of what was found. That first stage had been marked by the extensive surveys of areas of Scotland pioneered by the late Robert Smith in the 1890s, and Oliver’s large-scale beach surveys, by way of annual UCL field-classes at Bouche d’Erquy, in Brittany.

A memorial plaque is attached to a sarsen stone set at the point from which Tansley admired the view of Kingley Vale. The memorial was re-dedicated by the British Ecological Society, English Nature and the New Phytologist Trust 2005. This image is used with the kind permission of Natural England.

Tansley’s immediate object of greater co-ordination and, therefore, of self-consciousness of ecological effort, was met by William Smith (Robert’s brother and himself a pioneer of extensive mapping) in convening a Committee for the Survey and Study of British Vegetation in December 1904. It comprised the nine most active surveyors and was under Tansley’s chairmanship. Difficulties in securing publication of the vegetation maps accelerated the shift to the second element in the Committee’s title, and Tansley’s procedural approach, namely that of studying the vegetation dynamics and ecological processes behind what members had mapped so diligently135,136.

Sufficient had been achieved by way of published memoirs, papers and maps for Tansley to plan a five-week International Phytogeographical Excursion in 1911134. Committee members prepared ‘a kind of guide book’ to their study-areas, which were to be included in the Excursion. Tansley edited, or rather brought the whole together as a synthesis of what had already been discovered of Britain’s various plant communities within their various physical and human contexts. Publication of 'Types of British Vegetation' (1911) by the Cambridge University Press23, along with the praise of the eleven leading international botanists participating in the Excursion, encouraged the founding, in 1913, of a British Ecological Society, the first of its kind in the world, with Tansley as founder-president. The immediate object of the open membership was to secure sufficient subscription to publish a Journal of Ecology, of which Tansley (elected to the Royal Society in 1915) became its long-serving editor a year later.

Tansley was inclusive by temperament. He may have been one of the five ‘botanical bolsheviks’ to call, in the pages of New Phytologist in 1917, for ‘The reconstruction of elementary botanical teaching’32, but his purpose was not to topple comparative morphology, but rather to accommodate more fully the other parts ‘most essential to the healthy life of botany as a whole’103. It was a goal most effectively achieved through the writing of textbooks, his 'Practical Plant Ecology: A Guide for Beginners in Field Study of Plant Communities' being published in 192339. Tansley typically sought, on the occasion of his presidency of Section K of the British Association that same year, to transcend factionalism, holding out the prospect of a unity which came from synthesising in an entirely inclusive manner the specialisation which was coming to characterise botany. Not only would that help retain a sense of community within botany, but the student would be better prepared, whether in taking up pure botany or one of its many applications within agriculture and forestry42.

For Tansley, such retention of unity was all the more rewarding for the prospect of an ‘intimate co-operation between botanists and zoologists’. There would be at last ‘a really accurate knowledge’ of the composition, behaviour and history of what the Americans called the ‘biota’, and thereby ‘the first really trustworthy body of knowledge’ in prescribing ‘the solution to many of the great economic problems which face the modern human world’. The occasion for such a remark was Tansley’s review of Charles Elton’s ‘pioneering’ book 'Animal Ecology' of 192850. Such promise made Tansley all the more intolerant of what he perceived to be a lack of rigour. He had earlier welcomed Frederic Clements’ enthusiastic promotion of more exact measurement of the different habitat-factors. But it was Clements’ interpretation of such data acquired on plant succession, in terms of plant communities as super-organisms, which caused Tansley to rebuke him so publicly for notions of ‘holism’. Unless firmly rejected, there was risk of ridicule that would undermine the labours of British ecologists, such as William H. Pearsall, E. J. Salisbury and A. S. Watt (let alone the animal ecologists), whose studies had become exemplars of the rigour which Tansley had so long sought. Tansley turned rather to the philosophers of chemistry and mathematics for his concept of an ecosystem, whereby the climate, soils, plants and animals functioned as part of a system, each with a functional relationship with the other55.

Tansley’s appointment as Sherardian Professor of Botany at Oxford, in 1927, afforded opportunity to effect what he had advocated so long, both in revitalising the department and, through working with the departments of forestry and agriculture (rural economy), in instilling an ecological perspective in those directions. As chairman of the British Empire Vegetation Committee, established by the Imperial Botanical Congress, he had acted as editor of a volume 'Aims and Methods in the Study of Vegetation' in 1926. He wrote in the foreword of how, if the living resources of the Empire were to be adequately managed by their respective colonial agencies, there had first to be study of the incidence, behaviour and potential of the different organisms48. And yet, however relevant their findings, ecologists could never rival the trained forester and agronomist for employment in those industries. Charles Elton had recognised the ecologists’ primacy in another direction, namely in their safeguarding and management of wildlife as an integral part of the amenity and recreational value of the North American national parks.

In Britain, such opportunity for advocating national parks and nature reserves emerged through the lobbying of the various voluntary preservationist- and learned- societies for a wartime voice in the preparations for post-war reconstruction. Tansley’s object, both in those discussions and the later deliberations of ministerial committees, was to instil the rigour required in determining the purpose, location and management of a statutory series of nature reserves. The measure of his success, with Charles Elton, was the appointment by royal charter of a new research council, the Nature Conservancy. Its additional powers to provide expert advice, to acquire and manage national nature reserves, and to undertake the research relevant to those executive responsibilities, were conferred by the National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act of 1949137.

The view from Kingley Vale southward towards Chichester was regarded by Tansley as the finest in England. He ensured that Kingley Vale was protected when in 1952 it became one of the first National Nature Reserves to be acquired by the Nature Conservancy. Original photograph taken by Ian Alexander.

If a man may be judged in part by the company he keeps, there is perhaps a significance in George Macaulay Trevelyan being one of Tansley’s few close friends. Trevelyan, a near contemporary at Trinity College, was appointed Regius Professor of History from 1927 and, following retirement on age-grounds in 1940, Master of Trinity College. Tansley’s similar retirement in July 1937 had afforded him time to complete what began as a revision of 'Types of British Vegetation'23, and became his greatest work of synthesis, 'The British Islands and their Vegetation'60, published by Cambridge University Press in 1939, for which he was awarded the Linnean Society’s gold medal. It placed the field study of plants on what Tutin called ‘a broader, saner and more scientific basis’140. Trevelyan was meanwhile completing his English Social History, its broad sweep of national social life making him the nation’s historian-laureate. Its substantial royalties went to the National Trust, of which Trevelyan was both active council-member and benefactor109. Tansley perforce looked not to such voluntary bodies, but to government itself, both for the employment of ecologists and in the belief that the same large-scale national plans, which were being laid for post-war industry and transport, must also enable the country’s rural charm to be preserved. Tansley used Trevelyan’s much-quoted propagandist piece 'Must England’s Beauty Perish?'139 to introduce his own propagandist volume 'Our Heritage of Wild Nature: A Plea for Organized Nature Conservation', published by the Cambridge University Press in 194566. Tansley emphasised how an expertise and experience, on the part of government agencies, was no less required for the beauty and dignity of the countryside and coast, than it was in laying out and designing post-war cities and towns.

In pressing for what he called ‘the disinterested pursuit of knowledge’, and most obviously a pre-eminence for ecology, Tansley saw nothing contradictory or embarrassing in his emphasising how scientists were profoundly influenced by their own prejudices and circumstances. As he asserted, in his Herbert Spencer Lecture 'The values of science to humanity', which he gave before an Oxford-university audience in June 1942, no one could be entirely unmoved by the social conditions of their time, or by the particular experiences of their earlier life and environment. To Tansley, it was from such personal experience that scientists were well placed to recognise the intellectual, ethical, aesthetic and ultimately spiritual values that made ‘science indispensable in our complicated material world’63. The conferment of a knighthood upon Tansley, in 1950, acknowledged him as ‘the pioneer of the modern ecological approach to nature conservation’.

I am deeply grateful to Martin Tomlinson for his sharing with me recollections of his grandfather, Sir Arthur Tansley.

Arthur Tansley and psychoanalysis

By Laura Cameron, Queen’s University, Ontario, Canada.

People always are more than we know. Consider the life of Sir Arthur George Tansley. Although long honoured as an eminent British ecologist, only in the last decade have we begun to appreciate fully Tansley’s deep interest in the workings of the human mind. Psychoanalysis was the second of his life’s preoccupations and he became an important popularizer of the new science in the early twentieth century.

It is the seeming implausibility of Tansley’s involvement with Sigmund Freud that makes his story such an intriguing one for the history of science and psychoanalysis. After World War I, while lecturing in the Botany School at the University of Cambridge, Tansley wrote a best selling book on the ‘new psychology’81. It led him, dissatisfied with his career in botany – his hope of winning the Chair of Botany at Oxford had been snuffed out by that university’s traditionalists – to engage seriously with psychoanalysis. Of his distinguished patient, Sigmund Freud would write: ‘Tansley has started analysis last Saturday. I find a charming man in him, a nice type of the English scientist. It might be a gain to win him over to our science at the loss of botany.’126 With Tansley’s increasing immersion in psychoanalytic communities and writings came his resignation from the Botany School and further periods of intense personal conflict. As Tansley put it himself, in 1926, ‘…it was touch and go whether I became a professional psychoanalyst’ or took the Chair of Botany at Oxford which, in a reversal of fortunes, was now being offered to him105. Oxford would win out but psychoanalysis would continue to impact on Tansley’s life and thought, just as his involvement would have lasting effects in psychoanalytic circles.

An interest in psychology perhaps first manifested during Tansley’s undergraduate years at Trinity College, Cambridge (1890–1894) where, he recalled, he took part in the ‘…usual interminable discussions on the universe - on philosophy, psychology, religion, politics, art and sex.’105 Tansley counted the future philosopher Bertrand Russell amongst his college friends; informally he made a character study of Russell and gave counsel regarding his personal life106.

Although it was in botany that Tansley had begun his career (first teaching at University College London and then the University of Cambridge), he continued to follow developments in psychology through influential contacts such as his former student Bernard Hart, an asylum doctor and author of 'The Psychology of Insanity', first published in 1912. Tansley would mention Sigmund Freud in his botany lectures at Cambridge and even shared proofs of Hart’s book with undergraduates in his classes108. When WWI broke out, Tansley kept in touch with the Cambridge botany students and colleagues who went to join the British forces; several of them would be killed or suffer psychological effects of ‘shell-shock’. Tansley himself began service in London as a clerk in the Ministry of Munitions and it was during this period that he considerably deepened his knowledge of Freud’s work.

Tansley attributed this new intensity of interest to a dream107. Occurring sometime around 1916, Tansley’s dream and his own analysis of it impressed him so deeply that he resolved to read Freud’s published books, a task facilitated by his knowledge of German. In 1953, when asked to record for the Sigmund Freud Archives (later sited at the Library of Congress) his memories of his relationship with Freud and psychoanalysis, he wrote: ‘My interest in the whole subject was now thoroughly aroused, and after a good deal of thought I determined to write my own picture of it as it shaped itself in my mind.’107 This ‘picture’ was 'The New Psychology and its Relation to Life', published in June 192081. Tansley had captured the postwar enthusiasm for Freudianism and published one of the most celebrated surveys of the ‘new psychology’ to date. It was reprinted 10 times in four years, in the first three years selling more than 10,000 copies in the United Kingdom, more than 4,000 in the same period in the United States, and was translated into German and Swedish107.

Tansley was disconcerted by the response to his book. Feeling he could not give adequate answers to myriad requests for advice without further knowledge of psychoanalysis, Tansley asked Freud’s ‘lieutenant’ in London, Ernest Jones, for an introduction to Freud so that he could undergo analysis. Freud arranged for Tansley to spend three months in Vienna, from the end of March to June 1922. Upon returning to England, Tansley began to strengthen his psychoanalytic networks and played a major role in the Symposium on the Relations of Complex and Sentiment for the July 1922 meeting of the British Psychological Society. As he stressed here and later in a 1923 letter to the American plant ecologist Frederic Clements, outlining his view of the central issues in the field of psychology: ‘The question of the applicability of Freudian method to the ‘normal’ mind is doubtless the crucial question.’106

Tansley felt the pursuit of both psychology and ecology increased his power of work ‘…largely I think to the release of powers through emotional clarification…’ but, he lamented to Clements ‘…the double pull is a considerable strain.’107 In the late spring of 1923, Tansley resigned from the Cambridge Botany School and in September he moved to Vienna with his wife and daughters; his analysis with Freud resumed in late December. After returning to London in May 1924, Tansley would attend the Eighth International Psychoanalytic Congress in Salzburg. On Freud’s recommendation, he took on a psychoanalytic case, to acquaint himself fully with the discipline, and on 7 October 1925, he was elected to full membership of the British Psychoanalytic Society.

Tansley made his Freudian commitments public in a series of polemical exchanges defending psychoanalysis in the Nation and Athenaeum in 1925; the acrimonious debate began with his favourable review of Freud’s Case Histories (13 June, 8 August, 12 September). However, as the year passed, Tansley may have judged that as a non-medical biologist, his opportunities were beginning to appear limited in psychoanalytical circles. The international psychoanalytic movement was rapidly moving toward a system of Education Committees that marked the beginning of more strictly hierarchical institutions devoted to training professional, and frequently medically qualified, psychoanalysts108. At the same time, Tansley’s continuing ecological work was held in increasingly high regard and, in 1926, he accepted an invitation to re-apply for the Sherardian Chair of Botany at Oxford. Although his career path was now clear, Tansley remained a champion of psychoanalytic science, hoping for it to evolve as more of an ‘open city’89 than a ‘defensively stocked camp’, and left a number of unpublished psychoanalytic papers. Tansley’s final book, completed in 1952, was 'Mind and Life: An Essay in Simplification', an overarching synthesis of the twin preoccupations of his professional career87.

Tansley continued to correspond with Freud113 and Freudian circles. After Freud’s death, Tansley provided the Royal Society with a beautifully crafted obituary. Sir Harry Godwin, Tansley’s former student and esteemed colleague, perceptively noted that nearly all of the gifts that Tansley described in Freud were ones that he ‘unconsciously acknowledged’ as attributes they held in common: they were ‘full of attractive ironic humour and with a very pungent wit’ and ‘free from illusions about human nature’116. Godwin also related that Tansley, when asked at an Oxford gathering ‘to name the man who, since the birth of Christ, would prove to have had the most lasting influence upon the world, unhesitatingly chose Freud’. When pondering Tansley’s profound conflicts or potential connections between his ecological and psychological pursuits, no doubt that is a choice to keep in mind.

From social psychology to ecology

By Peder Anker, University of Oslo, Norway.

Peder is an historian of science, he obtained his PhD at the University of Harvard.

Arthur Tansley once amazed his botanical friends by arguing that the psychologist Sigmund Freud was the most important thinker since Jesus116. It was indeed remarkable statement for a man who is known for his contributions to the field of ecology. Yet Tansley was also a keen contributor to research on sex-psychology and I suggest here that some of his ecological thinking emerged from his work in social psychology.

Tansley, it is worth recalling, was educated at University College, London, in the 1890s in an environment of Fabian socialists who argued that science was worthless unless it was of some value to society. Though he was no radical, Tansley too strongly believed science should serve a social end and he often expressed sympathy with leftist views. As the Russian revolution advanced he was even accused of promoting ‘Botanical Bolshevism’ and in effect was denied a professorship at Oxford because of his (botanically) radical views103,104. Devastated by the conservative dons at Oxford he turned to psychology partly as a personal therapy, but also in order to be of some help in a society shattered by war. The result was his book 'New Psychology and its Relation to Life'81.

At the age of 49 Tansley experienced his first major public success; his book received flattering reviews in all major newspapers and intellectual journals. What caught the public’s attention was what several reviewers found to be a scandalous psychological explanation of God and sexual sin, about which Tansley soon found himself in the midst of controversy. The book soon became a bestseller.

Its success was partly due to Freud's theories being in vogue. Tansley's book was received in the larger audience as a thriller exposing hidden sexual forces in human societies. All the attention helped to establish Tansley as a scholar outside the closed circle of botanists and ecologists. He frequented psychology circles and lectured on Freud's theory of sexuality before the British Society for the Study of Sex-Psychology. His book was a popularized explanation of such clinical psychology, and aimed at a broad audience. He was taken by surprise, however, when he discovered that it was used as a textbook for students of the topic.

The book is largely a synthesis of Freud's psychology and a discussion (as the title suggests) of how it relates to life. The human mind, Tansley argues, follows the laws of biology, and these laws are allegedly best expressed in Freud's psychology. Tansley saw in that psychology a theory of how interactions of psychic energies search for an unconscious equilibrium within the mind and ultimately within society.

In 'New Psychology' Tansley outlines how the mind’s psychic energy constitutes a person's libido. The mind is not alone; its energy reaches other minds and hence creates social energies, clusters and networks. The mind's social life includes primary channels to secure biological needs, secondary utilitarian channels which measure psychic cost and benefit, and luxury channels for pure enjoyment of life. Most importantly, the economy of psychic energy must be in balance with its environment. A good mind always tries to restore a lost equilibrium, and a good leader always tries to create a well-organized herd out of a messy crowd in a society. It is likely that Tansley was inspired by Herbert Spencer, the eminent Victorian philosopher and social theorist (he coined the phrase ‘survival of the fittest’). Although Tansley does not specifically refer to Spencer, Tansley's writings about equilibrium of the mind and social herds clearly reflect Spencer's principles.

The primary force of the mind or the instincts is an ability to form systems in the form of either systems of the mind or social systems. Tansley's 'New Psychology' represents a blend of biology and mechanism. He seems to build on a long British tradition of explaining ethics in terms of sentiments and feelings instead of reason, although he places more emphasis on the social instinct than on private sentiment in traditional utilitarian epistemology.

After naturalizing the human mind in his psychology, Tansley turned towards a process of humanizing nature in his ecology. Such circular argument is most evident in a 1920 article written shortly after his book on psychology, where Tansley developed a method for the classification of vegetation based upon comparison with human communities34. Tansley coined and explained ecological terminology and taxonomy through a variety of analogies to social psychology: The development of plant associations finds its analogy to development of an individual organism; the phylogeny of plants recapitulates the ontogeny of human beings; the rise and fall of plant communities is analogous to the rise and fall of human civilizations; equilibrium in the environment is comparable with the equilibrium of the mind; and colonial terminology is useful in explaining the development of both human and plant societies.

Tansley did not offer a psychoanalytic explanation for his ecological studies. However, he did believe that a complex matter like the human mind or society could be explained in terms of simple biological processes, which in turn are based on physical and chemical laws of energy. The transfer of psychological terminology into the realm of botany was based on this assumption.

While pursuing his interest in psychology he also found time to publish 'Aims and Methods in the Study of Vegetation' with his friend Thomas F. Chipp48, a book that finally helped Tansley win, in 1927, the prestigious Sherardian Chair of botany at Oxford and a Fellowship at Magdalen College. His appointment was timely as ecology was much in vogue among Oxford’s biologists, who thought it could provide a new and better way of ordering nature, society and knowledge in a British Empire shattered by war.

Magdalen College, Oxford in 1925. Trees on the right hand side hide the Botany Department and professor’s house which are opposite the college. Courtesy of Oxfordshire County Council Photographic Archive.

At Oxford, Tansley soon became involved with philosophy because the University in general, and Magdalen College in particular, was the scene of an intense debate between the romantic idealist and the material realist philosophers. The leader among the idealists was John Alexander Smith who in his 1930 lectures on the heritage of idealism argued that truth about the real world could only be understood through studies in the history of thinking. His main intellectual ally was Robert George Collingwood, who argued that scientific knowledge was based on the history of 'The Idea of Nature', the title of his widely used textbook generated from his lectures given at Oxford in the early 1930s112. To understand the history of ideas was for him the precondition for understanding the nature of scientific truth, which ultimately could lead to revelation of the ultimate truth that is with God. What concerned Collingwood was a moral decay, and a flight from Christian values into the ethically and politically suspicious path of positivism and material realism he saw in Tansley’s work in ecology and psychology, which he believed led to an unforgiving technological line of reasoning.

The realists at Oxford were equally well represented. Most notable among them was the clinical neurologist and neurophysiologist Charles S. Sherrington, who won the Nobel Prize in 1932 for his work on nervous systems, and the tutor in zoology, John Zachary Young. They revitalized Tansley's interest in psychology, and together they would form a clique focussed on understanding the nerve systems of both humans and animals.

As editor of Journal of Ecology, Tansley received in 1934 a series of three long papers in defence of an idealist approach to ecology128,129,130. They were written by the South African ecologist John Phillips. He knew Phillips from the Fifth International Botanical Congress held in Cambridge in 1930 where Phillips had presented a paper, ‘The Biotic Community’127. This laid out an idealist foundation for ecological research based on the philosophy and racist politics of his fellow South African, Jan Christian Smuts, Prime Minister of South Africa from 1919 to 1924 and 1939 to 1948. As a young man, Smuts had been an enthusiastic botanist and had become his country’s leading expert on savanna grass. He coined the word ‘holism’, the fundamental factor operative towards the creation of wholes in the Universe138. Envisioning botany as a science that could unite the country through his philosophy of holisms, he, chillingly, added that although every organism is a whole, some are more ’significant wholes’ than others. Smuts was seen by Phillips and by Frederic Clements, the leading N. American ecologist, as an important thinker and a key patron of ecology.

Tansley’s response to Phillips’ and Clements’ botany came in his landmark paper, ‘Use and the abuse of vegetational concepts and terms’55, where he laid out the whole ecosystem concept. His approach to ecology was a progressive mechanistic alternative to the idealist biotic community concept of Phillips, whom he attacked in the strongest terms.

Psychology, sociology and ecology eventually complemented each other in Tansley’s mechanistic philosophy and, at least in ecology, it was his philosophy that prevailed.

This text is based on: Anker PJ. 2001. Imperial ecology: environmental order in the British Empire, 1895–1945. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Major events in the life of Arthur Tansley

1871 | Born 15 August, 33 Regent Square, London, to George and Amelia (née Lawrence). George taught at the Working Men’s College, Gt Ormond St. |

1883 | Preparatory School, Worthing, Sussex |

1886 | Highgate School, London |

1889 | Studied for the Intermediate Science examination, University College, London (UCL) |

1890 | Natural Sciences Tripos, Trinity College, Cambridge. Part I 1893, Part II 1894 (botany with zoology subsidiary) |

1893–1906 | Assistant professor of Botany, UCL. Assisted Professor FW Oliver with studies of coastal vegetation. |

1900 | Visited Ceylon (Sri Lanka), Malay peninsula and Egypt |

1902 | Founded the New Phytologist, which he edited until 1931 |

1903 | Married Edith Chick, 30 August at Branscombe, nr Honiton, Devon |

1904 | Daughter Katharine born. Founded the Central Committee for the Survey and Study of British Vegetation (i.e. British Vegetation Committee). Committee members formed the first Council of the British Ecological Society (BES) in 1913. |

1905 | Daughter Margaret born (3rd daughter, Helen, born 1909) |

1907 | Lecturer in botany, University of Cambridge until 1923 |

1911 | Organised the first International Phytogeographic Excursion |

1913 | First President of the BES, founded 12 April |

1915 | Elected Fellow of the Royal Society |

1917 | Editor of Journal of Ecology until 1937 |

1920 | Published The New Psychology in Relation to Life |

1922 | Visited Sigmund Freud in Vienna |

1923 | President Botanical Section K, British Association for the Advancement of Science. Resigned University lectureship and moved his family to Vienna. Studied under Freud. |

1924 | Returned to his home in Grantchester, Cambridge. At the Imperial Botanical Congress, was made Chairman of the British Empire Vegetation Committee. |

1927 | Appointed Sherardian Professor of Botany, University of Oxford |

1937 | Retired to Grantchester |

1938 | President of BES (second term) |

1941 | Awarded Gold Medal of the Linnean Society |

1942 | Appointed chair of the BES’s new committee on ‘Nature Conservation and Nature Reserves’ |

1945 | Vice-chair and chair of the government’s Wild Life Conservation Special Committee (associated with the ‘Hobhouse Committee’ exploring the establishment of National Parks). Recommended formation of the Nature Conservancy, which should establish National Nature Reserves. |

1947 | President of the Council for the Promotion of Field Studies (i.e. Field Studies Council) until 1953 |

1949 | Chairman of the new Nature Conservancy (which later evolved into the Natural Environment Research Council, now UKRI) |

1950 | Knighted |

1955 | Died 25 November at Grantchester (Edith died 1970) |

(chronological order)

1. Tansley AG. 1883. On the Cleveland District. Westbury House School Ephemeris 19: 69–70.

2. Tansley AG. 1896. The Stelar theory – a history and a criticism. Science Progress 5: 133–150.

3. Tansley AG. 1896. The Stelar theory – a history and a criticism. II. The metamorphosis of the stele. Science Progress 5: 215–226.

4. Tansley AG, Chick E. 1901. Notes on the conducting tissue-system in Bryophyta. Annals of Botany 15: 1–38.

5. Blackman FF, Tansley AG. 1902. A revision of the classification of the Green Algae. New Phytologist 1: 17–24.

6. Tansley AG. 1902. Ecological notes. New Phytologist 1: 84–85.

7. Tansley AG, Lulham RB. 1902. On a new type of fern-stele, and its probable phylogenetic relations. Annals of Botany 16: 157–164.

8. Chick E, Tansley AG. 1903. On the structure of Schizaea malacanna. Annals of Botany 17: 493–510.

9. Tansley AG, Lulham RB. 1904. The vascular system of the rhizome and leaf-trace of Pteris aquilina L., and Pteris incisa, Thunb., var. integrifolia Beddome. New Phytologist 3: 1-17.

10. Tansley AG, Thomas EM. 1904. Root structure in the central cylinder of the hypocotyl. New Phytologist 3: 104–106.

11. Tansley AG. 1904. The problems of ecology: research in British ecology. New Phytologist 3: 191–200.

12. Oliver FG, Tansley AG. 1904. Methods of surveying vegetation on a large scale. New Phytologist 3: 228–237.

13. Tansley AG, Fritsch FE. 1905. Sketches of vegetation at home and abroad: the flora of the Ceylon littoral. New Phytologist 4: 1–17, 27–55.

14. Tansley AG. 1905. Ecological expedition to the Bouche d’Erquy 1905. New Phytologist 4: 192–194.

15. Blackman FF, Tansley AG. 1905. Ecology in its physiological and phytotopographical aspects (Clements’ ‘Research methods in ecology’). New Phytologist 4: 199–203, 232–253.

16. Tansley AG, Lulham RBJ. 1905. A study of the vascular system of Matonia pectinata. Annals of Botany 19: 475–476.

17. Tansley AG. 1906. Some general aspects of the algae. A review of Morphologie und Biologie der Algen by Friedrich Oltmans. New Phytologist 5: 34–46.

18. Tansley AG. 1907-8. Lectures on the evolution of the filicinean vascular system. New Phytologist 6: 25–35, 53–68, 109–120, 135–147, 148–155, 187–203, 219–238, 253–269; 7: 1–16, 29–40. [A course of Advanced Lectures in Botany given for the University of London at University College in the Lent Term, 1907]

19. Moss CE, Rankin WM, Tansley AG. 1910. The woodlands of England. New Phytologist 9: 125, 130–131, 147.

20. Tansley AG. 1911. The International Phytogeographical Excursion in the British Isles. New Phytologist 10: 271–291.

21. Blackman FF, Tansley AG. 1911. Review of a textbook of botany for colleges and universities. Vol.1. Morphology and physiology by Coulter JM, Barnes CR, Cowles H. New Phytologist 10: 349–359.

22. Tansley AG. 1911. Medullary rays and the evolution of the herbaceous habit. A review of books by Eames AJ, Bailey IW, Thompson WP and Groom P. New Phytologist 10: 362–366.

23. Tansley AG. 1911. Types of British vegetation. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

[edited for, and published by, the Central Committee for the Survey and Study of British Vegetation: copies given to all those attending the International Phytogeographic Excursion, 1911].

24. Tansley AG. 1912. The forest of Provence. Gardeners Chronicle 51: 89–90, 112–113, 131.

25. Tansley AG. 1913. A universal classification of plant communities. Journal of Ecology 1: 27–42.

26. Tansley AG. 1913. Primary survey of the Peak District of Derbyshire. Journal of Ecology 1: 275–285.

27. Tansley AG. 1913–1914. The International Phytogeographic Excursion in America in 1913. New Phytologist 12: 322–336; 13: 325–333.

28. Tansley AG. 1913. In: Hampstead Heath: its geology and natural history. London, UK: T. Fisher Unwin, 87–92. [Cited by Tansley, p. 324, in The British Islands and their vegetation, 1939]

29. Tansley AG. 1914. Presidential address. Journal of Ecology 2: 194–203.

30. Thompson HS. 1914. Flowering plants of the Riviera: a descriptive account of 1800 of the more interesting species; with an introduction on Riviera vegetation by A. G. Tansley. London, UK: Longmans.

31.Tansley AG. 1916. The development of vegetation. Journal of Ecology 4: 198–204.

32. Blackman FF, Blackman VH, Keeble F, Oliver FW, Tansley AG. 1917. The reconstruction of elementary botanical teaching. New Phytologist 16: 241–252.

33. Tansley AG. 1917. On competition between Galium saxatile L. (G. hercynicum Weig.) and Galium sylvestre Poll (G. asperum Schreb.) on different types of soil. Journal of Ecology 5: 173–179.

34. Tansley AG.1920. The classification of vegetation and the concept of development. Journal of Ecology 8: 118–149.

35. Salisbury EJ, Tansley AG. 1921. The Durmast oak-woods (Querceta sessili-florae) of the Silurian and Malvernian strata near Malvern. Journal of Ecology 9: 19–38.

36. Tansley AG. 1922. Elements of plant biology. London, UK: Allen and Unwin. [revised by W. O. James, 1949]

37. Tansley AG. 1922. Studies of the vegetation of the English chalk: II. Early stages of redevelopment of woody vegetation on chalk grassland. Journal of Ecology 10: 168–177.

38. Tansley AG. 1922. The new Zurich-Montpellier school. Journal of Ecology 10: 241–248.

39. Tansley AG. 1923. Practical plant ecology: a guide for beginners in field study of plant communities. London, UK: Allen and Unwin. [Revised and enlarged as Introduction to Plant Ecology 1946; extended by A. J. Willis, 1973]

40. Tansley AG. 1924. The unification of pure botany. Nature 113: 85–88.

41. Flahault C, Juel O, Schröter C, Tansley AG. 1924. Eug. Warming: in memorium. Botanisk Tidsskrift 39: 45–56.

42. Tansley AG. 1924. Some aspects of the present position of botany. In: Report of the 91st meeting of the British Association, Liverpool, 1923. London, UK: John Murray, 240–260. [The text of Tansley’s address as President of Section K]

43. Tansley AG. 1925. Experiment in genetics (review of C. C. Hurst’s book with the same title). The Nation and the Athenaeum (3 Oct), 19–20.

44. Tansley AG. 1925. Summary of vegetational work and problems in the Dominions. In: Brooks FT, ed. Imperial Botanical Conference 1924. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 259–269.

45. Tansley AG. 1925. The vegetation of the southern English chalk (Obere Kreide-Formation). Festschrift Carl Schröter. Verüffentlichungen des Geobotanischen Institutes Rübel in Zürich 3: 406–430.

46. Tansley AG, Adamson RS. 1925. Studies of the vegetation of the English chalk: III the chalk grasslands of the Hampshire–Sussex border. Journal of Ecology 13: 177–223.

47. Tansley AG, Adamson RS. 1926. Studies of the vegetation of the English chalk: IV a preliminary survey of the chalk grasslands of the Sussex Downs. Journal of Ecology 14: 1–32.

48. Tansley AG, Chipp TF. 1926. Aims and methods in the study of vegetation. London, UK: Whitefriars Press. [Edited for and published by the British Empire Vegetation Committee and Crown Agents for the Colonies. Tansley and Chipp wrote most of Part I, Nature and Aims of the Study of Vegetation; Plant Communities; Factors of the Habitat; Training; Methods of Investigation; and Collecting].

49. Tansley AG. 1927. The future development and functions of the Oxford Department of Botany. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press.

50. Tansley AG. 1928. Reviews. Journal of Ecology 16: 163–71. [Books reviewed: Elton, C. Animal ecology, London, Sidgwick and Jackson; Rayner MC. Mycorrhiza, an account on non-pathogenic infection by Fungi in Vascular Plants and Bryophytes. New Phytologist reprint no.15; Audus JW. One of nature’s wonderlands, the Victorian Grampians. Melbourne, Australia: Ramsay.]

51. Tansley AG. 1929. Succession: the concept and its values. Proceedings of the International Congress of Plant Sciences, Ithaca. 1: 677. Manasha, Wis.: Banta.

52. Godwin H, Tansley AG. 1929. The vegetation of Wicken Fen. In: Gardiner S, ed. The natural history of Wicken Fen, part V. Cambridge, UK: Bowes & Bowes.

53. Tansley AG. 1931. Obituary notice: Charles Edward Moss. Journal of Ecology 19: 209–214.

54. Tansley AG, Watt AS. 1932. British beechwoods. Die Buchenwälder Europas, Verüffentlichungen des Geobotanischen Institutes Rübel in Zürich 3: 294–361.

55. Tansley AG. 1935. The use and abuse of vegetational concepts and terms. Ecology 16: 284–307. [Reprinted as part of Trudgill S. 2007. Classics in physical geography revisited, Tansley, A.G. 1935: The use and abuse of vegetational concepts and terms. Ecology 16: 284-307.]

56. Tansley AG. 1936. Prof. Frank Cavers. Nature 137: 1022.

57. Tansley AG. 1939. British ecology during the past quarter-century: The plant community and the ecosystem. Journal of Ecology 27: 513–530.

58. Tansley AG. 1939. Obituary: Carl Schröter, 1855–1939. Journal of Ecology 27: 531–534.

59. Tansley AG. 1939. Arthur Harry Church. 1865–1937. Obituary Notices of Fellows of the Royal Society 2: 433–443.

60. Tansley AG. 1939. The British Islands and their vegetation. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Reprinted in 1949 with corrections]

61. Tansley AG. 1940. Obituary: Henry Chandler Cowles, 1869–1939. Journal of Ecology 28: 450–452.

62. Tansley AG. 1940. Natural and semi-natural British woodlands. Forestry 14: 1–21.

63. Tansley AG. 1942. The values of science to humanity. Nature 150: 104–110. [Text of the Herbert Spencer Lecture: mainly psychology and philosophy]

64. Godwin H, Tansley AG. 1942. The vegetation of Wicken Fen. [Offprint No. 37 from an unidentified periodical. In stock at the Bodleian Library, Oxford University].

65. Tansley AG. 1943. Nature reserves. The Spectator, 519-520.

66. Tansley AG. 1945. Our heritage of wild nature: a plea for organized nature conservation. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

67. Tansley AG. 1946. Introduction to plant ecology. London, UK: Allen and Unwin. [Revision of Practical plant ecology, 1923]

68. Tansley AG. 1946. Discussion of fundamental research in relation to the community. Advancement of Science 3: 294–295.

69. Baker JR, Tansley AG. 1946. The course of the controversy on freedom in science. Nature 158: 574–576.

70. Tansley AG, Price Evans E. 1946. Plant ecology and the school. London, UK: Allen & Unwin.

71. Tansley AG. 1947. Obituary Notice. Frederick Edward Clements, 1874–1945. Journal of Ecology 34: 194–196.

72. Tansley AG. 1947. The early history of modern plant ecology in Britain. Journal of Ecology 35: 130–137.

73. Tansley AG. 1949. Britain’s green mantle: past, present, and future. London, UK: Allen and Unwin. [Revised by M. C. F. Proctor, 1968]

74. Tansley AG. 1951. What is ecology? Council for the Promotion of Field Studies. [Reprinted (1987) in the Biological Journal of the Linnean Society.]

75. Tansley AG. 1952. Oaks and oak woods. London, UK: Methuen. [For students at field study centres.]

76. Tansley AG. 1954. Some reminiscences. Vegetatio 5–6: vii–viii.

Notes

In addition, see reference 102 (below).

Book reviews are included where Tansley’s review added significantly to the subject.

As Editor of New Phytologist, Tansley also wrote anonymous contributions, reviewing local meetings or dealing with subjects as diverse as ‘The opening of the new botanical school at Cambridge’ (3: 61–63) and ‘The National Union of Scientific Workers’ (17: 1–2).

Tansley may have been short of copy for Volume 1 of New Phytologist for pages 121-124 contain a letter ‘To the Editor of the “New Phytologist” on ‘”Reduction” in descent’. The letter is signed by AG Tansley, University College, June 1902.

(in chronological order)

81. Tansley AG. 1920. The new psychology and its relation to life. London, UK: Allen and Unwin.

82. Tansley AG. 1922. The relations of complex and sentiment symposium. British Journal of Psychology 13: 113–122.

83. Tansley AG. 1924. Critical notice: Versuch einer Genitaltheorie: von Dr. S. Ferenczi. Journal of Medical Psychology 4:156–161.

84. Tansley AG. 1927. Review of C. J. Patten: the memory factor in biology. International Journal of Psychoanalysis 8: 292.

85. Tansley AG. 1927. Abstract of F.Teller: Libidotheorie und Artumwandlung. International Journal of Psychoanalysis 8: 531.

86. Tansley AG. 1939-41. Sigmund Freud, 1856–1939. Obituary Notices of Fellows of the Royal Society 3: 246–275.

87. Tansley AG. 1952. Mind and life: an essay in simplification. London, UK: Allen and Unwin.

88. Tansley AG. 1952. The psychological connexion of two basic principles of the SFS. Society for Freedom in Science, Occasional Pamphlet no.12.

89. Tansley AG. Unpublished. On criticisms of Freudian theory. [Mss. in the Tansley Archives of the Department of Plant Science, University of Cambridge: filed with other papers relating to the Magdalen Philosophy Club, so probably the text of a talk delivered in the 1930s. See Anker (2002)].

(alphabetical order)

101. Anker PJ. 2001. Imperial ecology: environmental order in the British Empire, 1895–1945. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

102. Anker PJ. 2002. The context of ecosystem theory. Ecosystems 5: 611–613.

[A philosophical contextualization of Tansley’s 1932 paper 'The temporal genetic series as a means of approach to philosophy,” which is also published for the first time.]

103. Boney AD. 1991. The ‘Tansley Manifesto’ affair. New Phytologist 118: 3–21.

104. Bower FO. 1918. Botanical bolshevism. New Phytologist 17: 106-107.

105. Cameron L. 1999. Histories of disturbance. Radical History Review 74: 2–24.

106. Cameron L. 2008. Sir Arthur George Tansley. In: Koertge N, ed. New Dictionary of Scientific Biography. London, UK: Thomson Gale, 3-10.

107. Cameron L, Forrester J. 1999. A nice type of the English scientist: Tansley and Freud. History Workshop Journal 48: 64-100.

[revised as Cameron L, Forrester J. 2004. A nice type of the English scientist: Tansley, Freud and a psychoanalytic dream’. In: Pick D, Roper L, eds. Dreams and history: the interpretation of dreams from Ancient Greece to modern psychoanalysis. London, UK: Routledge, 199-236.]

108. Cameron L, Forrester J. 2000. Tansley’s psychoanalytic network: an episode out of the early history of psychoanalysis in England. Psychoanalysis and History 2: 189–256.

109. Cannadine D. 2004. Trevelyan, George Macauley. New Dictionary of National Biography 55: 328-32.

110. Cassidy VM. 2007. Henry Chandler Cowles: pioneer ecologist. Chicago, IL, USA: Sigel Press.

111. Clements FE. 1916. Plant succession: an analysis of the development of vegetation. Washington DC, USA: Carnegie Institution of Washington Publication, 242.

112. Collingwood RG. 1944. Idea of nature. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

113. Forrester J, Cameron L. 1999. A cure with a defect: a previously unpublished letter by Freud concerning ‘Anna O’. International Journal of Psychoanalysis 80: 929–942.

114. Grime JP. 1979. Plant strategies and vegetation processes. Chichester, UK: J Wiley & Sons.

115. Godwin H. 1957. Arthur George Tansley, 1871–1955. Biographical memoirs of fellows of the Royal Society 3: 227–246.

[draws on ‘factual biographical notes’ written by A.G.T. for the Council of the Royal Society, 1953.]

116. Godwin H. 1977. Sir Arthur Tansley: the man and his subject. Journal of Ecology 65: 1–26.

117. Godwin H. 1985. Early development of the New Phytologist. New Phytologist 100: 1–4.

118. Harper JL. 1977. Population biology of plants. London, UK: Academic Press.

119. Körner C. 2001. Hundred years after A.F.W. Schimper – a founder of functional plant ecology. In: Zotz G, Körner C, eds. Funktionelle Bedeutung von Biodiversität – the functional importance of biodiversity. Verhandlungen der Gesellschaft für Ökologie vol. 31. Berlin, Germany: Parey Buchverlag, 7–9.

120. Körner C. 2003. Limitation and stress - always or never? Journal of Vegetation Science 14: 141-143.

121. Körner C. 2004. Individuals have limitations, not communities – a response to Marrs, Weiher and Lortie et al. Journal of Vegetation Science 15: 581-582.

122. Körner C. 2007. Climatic treelines: conventions, global patterns, causes. Erdkunde 61: 316-324.

123. Lewis DH, Ingram J. 2002. A brief history of New Phytologist. New Phytologist 153: 2-16.

124. MacArthur RH. 1972. Geographical ecology. Patterns in the distribution of species. London, UK: Harper & Row.

125. Oliver FW 1912. A letter. Tansley MSS. Library of the School of Life Sciences, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK.

[A testimonial written when Tansley considered applying for a Chair at the University of Adelaide – he never applied.]

126. Paskauskas A. 1993. The complete correspondence of Sigmund Freud and Ernest Jones, 1908–1939. Cambridge, MA, USA: Harvard University Press.

[The letter cited is from Freud to Jones on 6 April 1922.]

127. Phillips JFV. 1931. The biotic community. Journal of Ecology 19: 1-24.

128. Phillips JFV. 1934. Succession, development, the climax, and the complex organism: an analysis of concepts. Part I. Journal of Ecology 22, 554-571.

129. Phillips JFV. 1935. Succession, development, the climax, and the complex organism: an anlysis of concepts. Part II. Development and the climax. Journal of Ecology 23: 210–246.

130. Phillips JFV. 1935. Succession, development, the climax, and the complex organism: an analysis of concepts. Part III. The complex organism: conclusions. Journal of Ecology 23: 488–508.

131. Real LA, Brown JH. 1991. Foundations of ecology: classic papers with commentaries. Chicago, IL, USA: University of Chicago Press.

132. Schimper AFW. 1898. Pflanzen-Geographie auf Physiologischer Grundlage. Jena: G. Fischer.

[Translated into English in 1903 by P. Groom and I. B. Balfour. Plant Geography upon a physiological basis. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press.]

133. Schroeter C. 1908. Pflanzenleben der Alpen. Zürich, Switzerland: Albert Raustein.

134. Schulte Fischedick K, Shinn T. 1993. The international phytogeographical excursions, 1911–1923. In: Crawford E, Shinn T, Sörlin S, eds). Denationalising science. Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Kluwer Academic publishers:107–131.

135. Schulte Fischedick K. 2000. From survey to ecology: the role of the British Vegetation Committee, 1904–1913. Journal of the History of Biology 33: 291–314.

136. Sheail J. 1987. Seventy-five years in ecology: the British Ecological Society. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Scientific Publications.

137. Sheail J. 1998. Nature cconservation in Britain: the formative years. London, UK: The Stationery Office.

138. Smuts JC. 1926. Holism and evolution. London, UK: Macmillan.

139. Trevelyan GM. 1929. Must England’s beauty perish? A plea on the behalf of the National Trust for places of historic interest or natural beauty. London, UK: Faber and Gwyer.

140. Tutin TG. 1956-7. Arthur George Tansley. Proceedings of the Botanical Society of the British Isles 2: 99–100.

141. Warming JEB. 1896. Lehrbuch der ökologischen Pflanzengeographie. Eine Einführung in die Kenntnis der Pflanzenvereine. Berlin, Germany: Borntraeger.

[Translated into English in 1909 by P. Groom and I. B. Balfour. Oecology of plants: an introduction to the study of plant communities. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press.]